Amblyopia (“Lazy Eye”)

Amblyopia

(“lazy eye”) is poor transmission of the visual image to the brain. It affects

as many as 380,000 children in the United States and will lead to lifelong

visual impairment if not identified and treated in early childhood. An

amblyopic eye will never develop good vision and may even become functionally

blind. Unfortunately, few children are screened for strabismus (misalignment of

the eyes) or defocus (blurred vision), the two primary causes of amblyopia.

* Amblyopia, otherwise known as lazy eye,

is a disorder of the visual system that is characterized by poor or indistinct

vision in an eye that is otherwise physically normal.

* The problem arises from chronic suppression by the brain of the

visual image from a blurred or misaligned eye.

* The term "lazy eye“, frequently

used to refer to amblyopia, is inaccurate because there is no

"laziness" of either the eye or the person with this condition.

"Lazy brain" is a more accurate term to describe amblyopia.

Detecting risk for amblyopia.

While automated screening tools exist, very few are effective in truly

detecting where the eyes are looking. The novel technology we are developing is

able to tell when both eyes are looking in the desired direction by detecting

the actual fovea of each eye – the part of the retina that we aim at objects

when we look at them. With a hand-held instrument from 12 inches away, we scan

the retina with a spot of polarized near-infrared light in a circle, a

technique we call “retinal birefringence scanning” (RBS). Our Pediatric Vision

Screener will combine a new version of RBS for detecting strabismus accurately,

with added technology for assessing proper focus of both eyes simultaneously,

and optimized electronics and signal processing to ensure high-quality signals.

By enabling early identification and treatment of children at risk for

amblyopia, this instrument has the potential to prevent lifelong disability

from a readily treatable condition.

Amblyopia is poor vision in what

appears to be a normal eye. It arises from defective visual input to the brain

during infancy and childhood, leading to abnormal development of the binocular

visual system. One of the two primary causes, or risk factors, for amblyopia is

misalignment of the eyes, or strabismus. In strabismus, the brain in

childhood may suppress the input from one eye to avoid double vision or visual

confusion. Such visual suppression interferes with normal binocular visual

development and may cause irreversible poor vision extending into adulthood.

The other major risk factor for amblyopia, defocus,

occurs in either of two ways. When there is a significantly different

refractive error between the two eyes (anisometropia),

there is a discrepancy in the focus between the two eyes that can lead to

amblyopia in the defocused eye. The second type of defocus occurs in the case

of visual deprivation, such as when there is a high level of refractive error

in both eyes or when there are obstacles in an eye’s line of sight, such as

congenital cataracts or drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis).

Amblyopia is poor vision in what

appears to be a normal eye. It arises from defective visual input to the brain

during infancy and childhood, leading to abnormal development of the binocular

visual system. One of the two primary causes, or risk factors, for amblyopia is

misalignment of the eyes, or strabismus. In strabismus, the brain in

childhood may suppress the input from one eye to avoid double vision or visual

confusion. Such visual suppression interferes with normal binocular visual

development and may cause irreversible poor vision extending into adulthood.

The other major risk factor for amblyopia, defocus,

occurs in either of two ways. When there is a significantly different

refractive error between the two eyes (anisometropia),

there is a discrepancy in the focus between the two eyes that can lead to

amblyopia in the defocused eye. The second type of defocus occurs in the case

of visual deprivation, such as when there is a high level of refractive error

in both eyes or when there are obstacles in an eye’s line of sight, such as

congenital cataracts or drooping of the upper eyelid (ptosis).

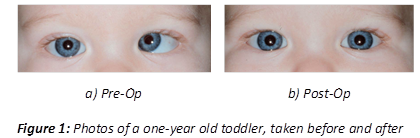

Amblyopia is a major public health

problem, with impairment estimated to afflict up to 3.6% of children – and more

in medically underserved populations. Amblyopia is also among the top three

causes of visual impairment in adults. Of particular significance is that

amblyopia can be successfully treated, but only in early childhood, especially

during infancy. Figure 1 shows the successful surgical elimination of

strabismus, a primary cause of amblyopia, in a one-year-old child. Delayed

treatment risks lifelong visual impairment. Assuming a prevalence of 2% in the

19 million children less than five years of age in the United States, there are

at any given time 380,000 children with amblyopia. Only a fraction of these

children will be screened. Only six states in the Unites States require

preschool vision screening for all children, and a population study in Great

Britain found that only 15% of children with anisometropia

were identified before the age of 5 years. And even where screening does take

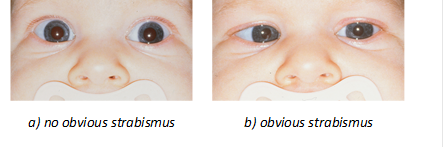

place, the devices used do not work reliably with young children. As Figure 2

shows, it is not always easy to identify strabismus in youngsters at risk for

amblyopia. Recent years have seen the introduction of electro-optical

instruments that make objective screening possible, and in some cases provide

automated analysis of the results of a given child’s screen. However, many of these

devices have problems of their own that constrain their effectiveness,

especially when judged against the high level of performance (e.g. sensitivity

and specificity) required to justify screening in the current environment of

limited health care resources. Several devices are being evaluated in clinical

environment. Please click

here for more information on our

pediatric vision screeners.

Figure 2. Two images of the eyes of a strabismic patient, taken several seconds apart. Strabismus is obvious in the second picture, but not obvious at all in the first image. This presents a challenge in automated screening.